How to deter China and prevent future standoffs? A research paper suggests continued talks but that may not be enough – Firstpost

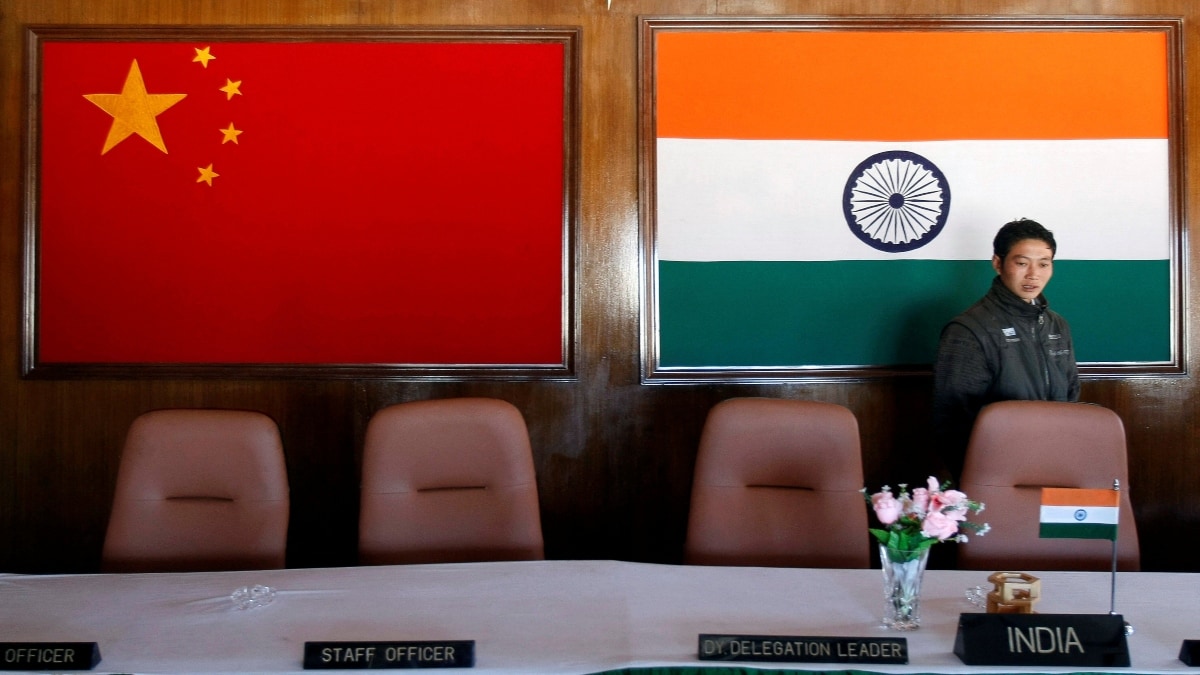

It seems a cliché to observe that India-China relationship is at a crossroads. Since April-May 2020, the giant Asian neighbours have been lurching from one crisis to another. And yet, not many would have wagered during the depths of the Galwan tragedy that both nations would arrive at a détente within four years of that calamity.

In fact, 2024 ended on a note of rare optimism for both sides. Painstaking negotiations finally bore fruit as the last two remaining friction points in eastern Ladakh, Depsang and Demchok, eased into a resolution and a new set of arrangements was worked out. Troops pulled back to positions held before April 2020, disengagement was achieved through a verifiable step-by-step process and patrolling rights were restored. The two sides even exchanged sweets on Diwali.

An Indian inter-ministerial panel even cleared a few investment proposals in the electronics manufacturing sector for Chinese players, reflecting the improving sentiment. It may have also been a tacit admission from policymakers in New Delhi that preventing the influx of Chinese capital, technology and talent has had a deleterious effect on local industries that have struggled to scale up or even survive in absence of access to Chinese supply chains.

Beijing wasted no time in pushing for resumption of direct flights in light of the thaw, but India has so far been hesitant. The hard-earned gains at the border have showed the value of diplomacy and mature leadership, but trust is still in short supply. The uneasy calm in the backdrop of 100,000 troops and their state-of-the-art fighting gear is still a far cry from the peace and tranquility that was destroyed by Chinese adventurism at multiple points along the LAC in April-May 2020.

The cessation of forward deployments, creation of demilitarized zones, buffer zones or areas of limited patrolling, disengagement of troops leading to de-escalation and/or dismantling of structures along the LAC cannot immediately translate into normalization of ties, resumption of bilateral exchanges, reduction of tension and restoration of mutual trust.

To quote former foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale in India Today, “There is no guarantee that peace and tranquility will prevail along the LAC in 2025. China still thinks grey zone warfare is a cheap option to place fetters on India without serious backlash. Talk-and-deter must continue to remain the dual approach to dealing with China.”

This sentiment runs across the length and breadth of the Indian state and its armed forces. The Indian side anticipates sudden escalation of hostilities and creation of new friction points along the LAC in absence of strategic trust and de-escalation of troops, and an overwhelming stabilization factor that may reduce the likelihood of a kinetic conflict. Right now, strategic logic leans towards confrontation as the ‘new normal’ that must be managed through careful diplomacy.

During the Army Day celebrations on January 15, for instance, COAS General Upendra Dwivedi told the media that while disengagement has been achieved in the two friction points at Eastern Ladakh in October last year, the standoff is not yet over. “The terrain has been doctored by both sides, and while temporary moratoriums are maintained in buffer zones, further negotiations are essential for long-term resolution.”

External affairs minister S Jaishankar, while apprising the Lok Sabha on December 3 on the agreement with China to disengage troops at Demchok and Depsang in Eastern Ladakh, said, “we were and we remain very clear that the three key principles must be observed in all circumstances: (i) both sides should strictly respect and observe the LAC, (ii) neither side should attempt to unilaterally alter the status quo, and (iii) agreements and understandings reached in the past must be fully abided by in their entirety.”

The minister expanded on his remarks at Saturday’s Nani Palkhivala Memorial lecture in Mumbai, where he said, “At a time when most of its relationships are moving forward, India confronts a particular challenge in establishing an equilibrium with China… Right now, the relationship is trying to disentangle itself from the complications arising from the post-2020 border situation. Even as that is being addressed, more thought needs to be given to the longer-term evolution of ties. Clearly, India has to prepare for expressions of China’s growing capabilities, particularly those that impinge directly on our interests.”

This scepticism, despite the forward movement achieved through painstaking diplomacy, is warranted. A snapshot of the latest developments indicates the myriad ways in which China poses a relentless challenge to the Indian state.

Beijing has of late taken to imposing unofficial and undeclared ‘sanctions’ on India in the electronics, solar, and electric vehicle (EV) sectors where Indian firms are experiencing delays and disruptions due to China’s restrictions on export of key inputs and machinery, Economic Times reported last week quoting GTRI, a think tank.

India’s imports from China, meanwhile, increased to $101.73 billion in 2023-24 from $98.5 billion in 2022-23, reflecting New Delhi’s inability in diversifying its supply chain and the handing of a potent economic weapon to Beijing.

In recent times, China has also announced the building of the world’s largest dam, a $137 billion hydropower project on the upstream Yarlung Tsangpo river in Tibet that enters India as Brahmaputra. The dam, that may generate more than 300 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually according to estimates by South China Morning Post, poses tremendous challenges to India – the lower riparian nation – in absence of a water-sharing treaty. Nothing stops Beijing from weaponizing the dam on a river on which India is critically dependent for drinking water, irrigation and generation of hydroelectricity.

India has also lodged a formal protest in the New Year with China over the formation of two ‘counties’ at ‘Hotan prefecture’ that infringe on India’s sovereignty in Aksai Chin. An MEA spokesperson said “we have never accepted the illegal Chinese occupation of Indian territory in this area. Creation of new counties will neither have a bearing on India’s long-standing and consistent position regarding our sovereignty over the area nor lend legitimacy to China’s illegal and forcible occupation of the same.”

In this atmosphere of mistrust, coercion and competition interspersed with negotiation and cooperation, it is of vital importance that the India-China rivalry is perceived in public domain through the correct analytical framework.

India has a sharp, experienced and dedicated community of ‘China watchers’, consisting chiefly of military officers (retired or active), but their valuable research output is consumed in-house within the government and remains out of bounds for the public.

It is refreshing to see, therefore, a new crop of researchers in private and think tank space ready to do due diligence that this discipline deserves. I recently went through a paper,

Negotiating the India-China Standoff: 2020–2024, by Saheb Singh Chadha of Carnegie India, who delivers a comprehensive analysis of the India-China border standoff from April-May 2020 to October 2024.

Chadha’s research aims to bridge a critical gap, as he puts it, in exploring the “negotiating positions of both sides across the four years of the standoff.” Chadha believes few works “compare official statements across time and between the two countries. Analysis of Chinese statements and sources is particularly rare.”

The author relies on four types of resources for his work. Close textual observations of primary sources that are ‘official statements’ released after interactions between the two sides “through three channels—the Senior Highest Military Commander Level (SHMCL) talks, the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC) at the diplomatic level, and the meetings at the politico-strategic level between heads of state, foreign ministers, defense ministers, national security advisors, and special representatives on the India-China boundary question.”

He also follows official statements by government representatives, conducts interviews with stakeholders in GOI “who have been involved in negotiations and decision-making on the standoff or have knowledge of India-China military dynamics along the border”, and media reports.

This analytical discipline leads him to observe that “it is possible to divide the past four years of the standoff into three phases based on the negotiating positions of both sides. Between April and September 2020, both sides sought to manage the crisis, reduce tensions, and avoid a fatal clash akin to the Galwan incident”.

“Between September 2020 and September 2022, both sides negotiated disengagement in four friction points in eastern Ladakh.”

“Between September 2022 and July 2024, the gaps in their positions were visible. China signaled its unwillingness to disengage in Depsang and Demchok, preferring to treat them as legacy issues and wanting both sides to ‘turn over a new leaf’ for the border situation” whereas “India stood by its demand for complete disengagement and de-escalation of troops, and restoration of patrolling rights in Depsang and Demchok before broader bilateral exchanges could deepen.”

“The two sides have attempted to find consensus since July 2024 and, as a result, the situation underwent a change from October to December 2024.”

The author posits that “India and China are faced with a classical security dilemma” since China sees in India’s infrastructure build-up at the LAC an American ploy to contain it in the Indo-Pacific, whereas “India views the development of border infrastructure as necessary for its security and the deepening of India–U.S. relations as necessary for its development and security.”

The paper recommends creation of a “new modus vivendi” and the developing of a new mutual political understanding to avoid slipping into a kinetic conflict and address the trust deficit, and identifies continued dialogue at the “politico-strategic level” to “to push for further resolution of the standoff and to use it as a path to pursue trust-building between the two sides.”

It is questionable whether dialogue alone (regardless of the level where it is held at) would be enough to reintroduce mutual trust and prevent a relapse of the clashes between the two sides since China sees in the LAC kerfuffle a low-cost, dynamic option to keep India unstable.

Also, since the gap between the two sides in terms of national composite power is substantial and widening – and given the fact that China lacks an incentive to pause adventurism along the LAC – talks alone may not be an effective enough deterrent.

The best deterrent for India is a mix of external and internal balancing, with a desperate focus on accelerating internal growth, launching reforms, addressing inequality, de-risking and diversifying supply chains to boost manufacturing and build deep strengths.

The writer is Deputy Executive Editor, Firstpost. He tweets as @sreemoytalukdar. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

Post Comment