Soft power, strong gains – Firstpost

The Third China-Indian Ocean Region Forum on Blue Economy Development Cooperation was held from December 15 to 17 in Kunming. Apart from the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), the principal organiser, it is notable that Barbados and the Maldives co-hosted the forum alongside China. The forum, themed “Future of the Blue Indian Ocean—Development Practice of the Global South,” featured, for the first time, a dialogue between governments and enterprises. Representatives from Chinese and international governments, as well as companies, discussed multi-stakeholder engagement in international development cooperation, paving the way for broader international collaboration by involving multiple stakeholders.

Zhao Fengtao, Deputy Director of the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), said, “Next, we are willing to deepen opening-up and cooperation with other countries to jointly create a ’new engine’ for the blue economy. We will consolidate consensus on sustainable marine development to build a ’new space’ for blue development. Maritime dialogue and consultations will be strengthened to seek a ’new model’ for blue governance. We will also promote mutual learning among maritime cultures with other countries to create a ’new chapter’ of maritime civilisation.”

Speaking at the opening ceremony, Wang Yong, Vice Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, mentioned that the “construction of a maritime community with a shared future” is evolving from a Chinese initiative into a shared international goal. China aims to enhance partnerships in maritime transport, biomedicine, renewable energy, infrastructure, and marine science and technology, Wang added.

At the third forum, a ‘Global Development Project Pool Information Management System’ was launched, along with the inauguration of the ‘China-Indian Ocean Region Centre for Maritime Cooperation and Training Centre’. Agreements were signed for the creation of a low-carbon demonstration zone in Seychelles and the development of projects for early warning and response to climate-induced disasters in Pakistan and the Maldives.

According to CIDCA, which organised the event, “China has established normalised cooperation mechanisms with 17 Indian Ocean region countries, and cooperation is being carried out in fields including remote sensing, maritime monitoring and research, biodiversity, and disaster reduction.” The forum prominently featured topics such as ocean-based infrastructure, digital empowerment for the blue economy, cultural exchange for marine tourism, automated port projects, automated warehouses, and distribution centres. Additionally, Chu Yili from China Communications Construction Company Ltd highlighted opportunities for joint development in marine new energy and deep-sea resource exploration.

‘Maritime Community with a Shared Future’ represents China’s broad vision for ocean-based economic development, through which it seeks to lead global oceanic and fisheries governance. Under this vision of a ‘shared future’, China aims to establish diverse mechanisms with a heightened focus on multi-tiered ocean governance in the Indian Ocean Region. To achieve these objectives, China advocates for maritime peace, joint governance of oceans, cooperation in fisheries management, support for marine technologies, and the development of information-sharing mechanisms.

It is worth recalling the deliverables outlined in the joint statement at the second China-Indian Ocean Region Forum on Development Cooperation (2023). These include establishing the China-Indian Ocean Region Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Alliance; building and initiating the China-Indian Ocean Region Blue Economy Think Tank Network; inaugurating the China-Africa Cooperation Centre on Satellite Remote Sensing Application in Beijing (July 2023); launching the Blue Talent Program; and proposing a New Energy Indian Ocean Initiative, among others.

The China-Africa Cooperation Centre on Satellite Remote Sensing Application stands out as a significant initiative, with clear potential for expansion in the coming years. Notably, China has launched the first satellites for its ‘GuoWang’ mega constellation (GuoWang meaning “national network”), intensifying the race for space-based broadband internet services both domestically and internationally. The project is managed by China Satellite Network Group Co. Ltd., a state-owned enterprise established in 2021 under the State Council, China’s cabinet.

The newly launched satellites mark the first batch of the GuoWang broadband mega constellation in low Earth orbit (LEO), which is planned to consist of nearly 13,000 spacecraft upon completion. Additionally, another Chinese broadband mega constellation, Qianfan (“Thousand Sails”), is also under development. Qianfan is expected to feature a similar scale, and to date, 54 Qianfan spacecraft have been launched across three missions conducted this year.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is particularly well-suited for all types of remote sensing, ranging from high-resolution Earth observation to scientific research. Thanks to technological advancements, various types of remote sensing satellites can operate in one of three orbits: polar, non-polar Low Earth Orbit (LEO), or Geostationary Orbit (GEO). The high number of satellites planned by Beijing allows for complete global coverage.

Understanding China’s Civil-Military Fusion (CMF) policy is key to recognising that advancements in LEO connectivity have not only enhanced civilian applications but have also triggered a paradigm shift in military communications. Orbiting at lower altitudes, LEO satellites offer low latency, enabling near-instantaneous connectivity for troops. This capability is a game-changer for personnel in the field, at sea, or even in the air, allowing them to make video calls, access critical data, and engage in seamless communication with minimal delay.

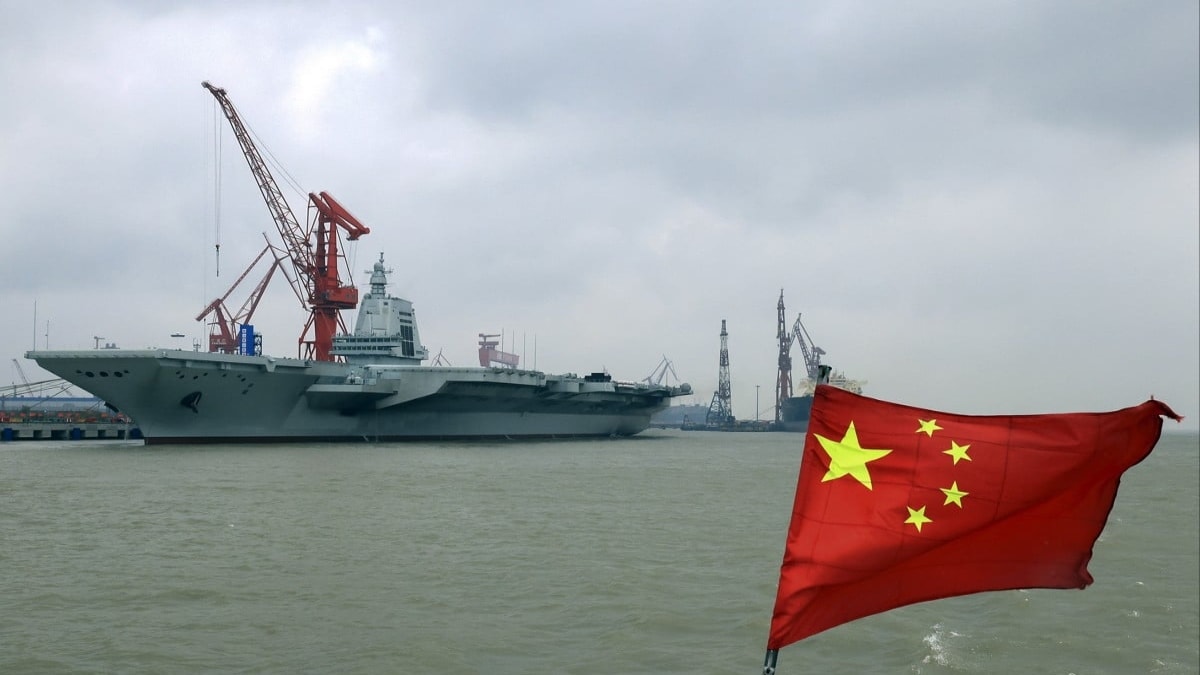

China’s approach to the ‘blue economy’ reflects a convergence of geopolitical, economic, ecological, technological, and legal perspectives, presenting emerging challenges for global ocean governance. These challenges arise from China’s integration of the blue economy development concept with its Maritime Silk Road initiative, through which it seeks to shape governance rules to align with its strategic interests. China views the ocean as an integral part of its maritime economy, positioning it as a driver of innovation to advance its goal of becoming a great maritime power. This vision aligns with the broader objectives of the Chinese Dream and national rejuvenation.

Under Xi Jinping, China aims to enhance maritime trade with the rest of the world, ensure food and energy security, and increase Chinese investments in port and ocean economy-related infrastructure globally. This culminated in the announcement of Beijing’s Vision for Maritime Cooperation in 2017. Since then, China’s Blue Economy concept has evolved into a core component of Beijing’s broader strategy to become a “global maritime great power”.

These efforts give China’s approach a global dimension and connect it to a broader Chinese discourse, linking outward-facing policies such as its claim of being a “near-Arctic state” in its Arctic policy. It also extends the One Belt and One Road Initiative (BRI) to include projects like the Health Silk Road, Space Silk Road, Arctic Silk Road, and Digital Silk Road, among others. Such discourses have reinforced China’s hardened positions in its maritime disputes with neighbouring countries in the South China Sea, including the Philippines, Vietnam, and others, positions that are widely regarded as unfounded and illegal.

Next, areas like cultural exchange and maritime tourism, though prominently discussed, need to be approached with caution. They create favourable conditions for China to exert influence and strategically position itself. This can lead to a more dominant Chinese presence and may pressure the respective governments to approve Beijing-initiated infrastructure plans with minimal resistance. In return, this facilitates China’s efforts to consolidate the presence of its companies in these regions.

China’s Ministry of State Security (Guoanbu) has consistently prioritised cultural soft power and people-to-people exchanges to maintain open channels of communication. In the past, it has devised plans to engage foreign personalities from academic, think tank, and cultural sectors to promote a vision of a benign China—one that poses no threat and positions itself solely as a development partner, aligning with the narrative of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). China’s efforts to develop new forms of ties, such as cultural diplomacy, should also be viewed through the lens of the United Front Work Department’s involvement. This CCP organ, known for its overseas influence operations, often operates under the guise of diplomatic channels.

Initiatives like the China-Indian Ocean Region Forum and the China-South Asia Cooperation Forum (CSACF) are part of Beijing’s soft power approach beyond military engagement, focusing on civil-diplomatic efforts to achieve preferred outcomes. Both of these initiatives exclude India, and China uses tools such as aid, capacity building, and advancements in science, technology, and innovation to strengthen its connections with countries in the Indo-Pacific and deepen its influence. In doing so, China also incentivises these countries to reduce their ties with India.

China relies on a safe, secure, and stable Indian Ocean to achieve its foreign policy and domestic objectives. Its interest in the region is clear, and the strategic importance of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) to China will only continue to grow. This can be seen as part of a new role that Beijing seeks to play in the IOR. These international activities and aspirations are expected to expand in the future.

The writer is the Head of Strategic Studies Programme at the Centre for National Security Studies (CNSS), Bengaluru. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

Post Comment