What Dhaka’s anti-India posturing means for the region’s security – Firstpost

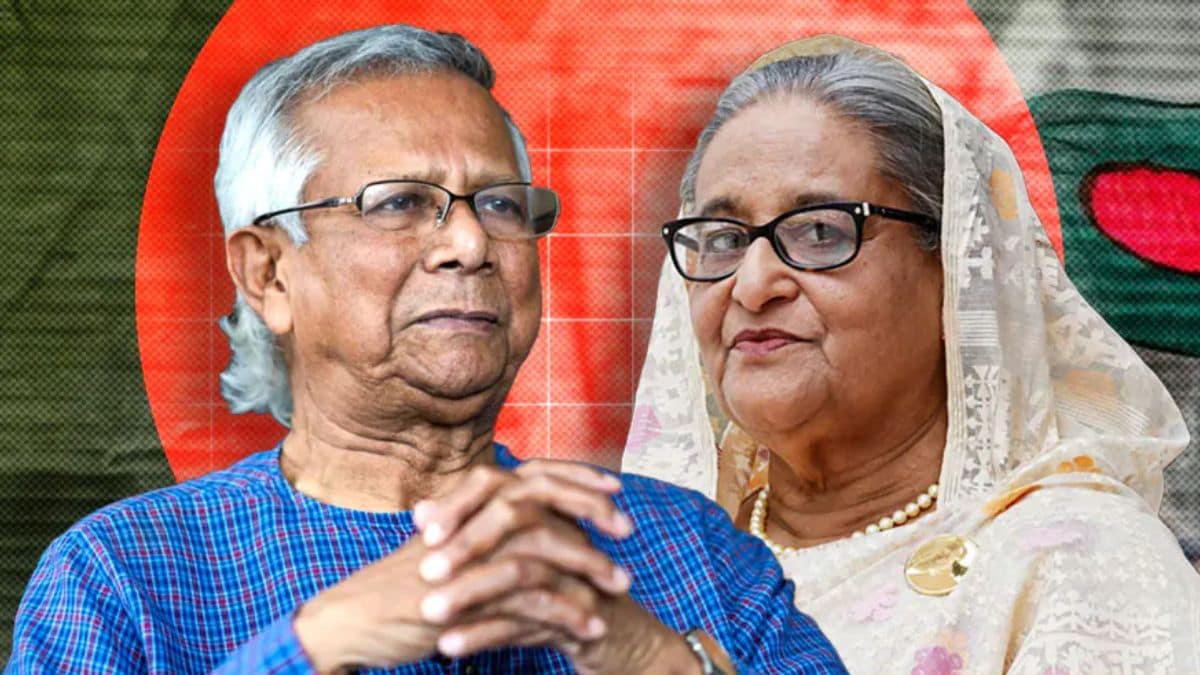

As was to be anticipated, the India-Bangladesh ties are more strained than most optimists in the two countries might have imagined in the days after the popular ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. In the latest in a series, the Bangladesh mission in New Delhi handed over a note verbale to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) for Hasina’s extradition, for ultimately standing trial in about a hundred criminal cases that include murder, genocide, and more.

Simultaneously, as if to provoke India even more, the so-called interim government of ‘chief advisor’ Muhammad Yunus has hugged one-time Pakistani tormentor, on trade and cultural ties, almost overnight. Over the medium and long terms, this can have consequences for regional security all along India’s land borders even otherwise. It means much more considering that Beijing is yet to restore the pre-Galwan confidence in New Delhi that long-pending border disputes and other bilateral issues would be resolved only through negotiations and not otherwise.

A note verbale is an unsigned third-person diplomatic intimation that is handed over in person, indicating scaled-up action if not acted upon. The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has acknowledged the receipt of the same but without comments. As if in response, a Bangladesh Foreign Ministry spokesman said that they would give India ‘certain time’ for a response before initiating further action. In particular, he told newsmen in Dhaka not to say things on a ‘sensitive’ matter like this one.

Before the note verbale, the Bangladesh Home Ministry had written to the MEA, seeking Hasina’s extradition, indicating that the former was the second in a possible series. India’s stony yet studied silence in the matter makes the next step, if any, as much critical as it may be curious. For Hasina, the irony flows from the fact that the warrant for her arrest flows from the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), constituted by her government, to try, execute, or otherwise punish ‘war criminals’ from the nation’s Liberation War in 1971.

Balancing act

For India, Hasina’s extradition is a moral question after it had allowed the Dalai Lama to settle down in the country when China annexed Tibet decades ago. India has played the balancing act pretty well by recognising Tibet to be a part of China and yet giving political asylum to the Dalai Lama. That India and China fought the 1962 war and have faced border skirmishes, big and small, since has not altered the ground position on Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

The question thus is if India can play it out likewise in the case of Bangladesh and Hasina. When in early August, mass protests forced her to quit (she still claims not to have resigned as PM) and fly or flee to India, the general expectation was that she would seek and obtain ‘political asylum’ in one of the West Asian countries and that India was only a ‘transit point’. But it is not so anymore. Reports have it that no other country wants to have her around, owing also possibly to their not wanting to irritate or provoke the new regime in Dhaka.

The sub-questions that flow from such a construct are for real: Did India anticipate such rejection of asylum pleas from European and West Asian countries when Hasina reportedly approached them? Will External Affairs Minister (EAM) S Jaishankar, now on a six-day US visit, only weeks ahead of the President-elect taking over on January 20, seek Washington’s issue to break what is emerging as a diplomatic deadlock between the two South Asian neighbours?

It is not easy for the new rulers in Dhaka to climb down on the extradition plea. Their locus standi for capturing power and continuing there without any fixed deadline for fresh parliamentary elections hinges on putting Hasina on trial. It is another matter that a section of the government’s supporters, especially from the Islamists’ ranks, will not compromise.

They have not forgiven Hasina for her government targeting them, both in the name of punishing ‘war criminals’ and in seeking extermination of religious terrorism, which had initially facilitated anti-India terrorism identified with Pakistan’s ISI. The cases were based on their aiding and abetting the Pakistani army in mass rapes and murders committed in the weeks preceding the liberation of Bangladesh. In a way, their flexing their muscles more than any other group during the weeks-long violent protests that led to her forced exit also owes to this ‘historic’ fact.

Cultural differences

Yes, it is this version of ‘Bangladeshi nationalism’ (sic) that has now inspired at least one advisor/minister telling India and Prime Minister Narendra Modi that it was the ‘Victory Day’ of his nation on 16 December (and not that of the larger neighbour, who burnt millions and lost their soldiers). According to him, India only assisted in the liberation—something that even he could not ignore or overlook or run down in ways that would have pleased the Islamists and also Islamabad.

But there is no denying that Bangladesh and Pakistan are mending fences full-time after the former sliced itself out of the latter in the early seventies. Yunus has met with Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif twice already since becoming chief advisor, one each in November and December. The latest meeting was held on the side-lines of D-8 Organisation of Economic Cooperation in Dubai.

What is surprising is the speed with which Islamabad has wrested the initiative on extending trade and economic assistance to Bangladesh when Pakistan itself is reeling under an extended economic crisis, with which the people are getting habituated to, without any real relief in sight. Already, two container ships, the recent one with 1,000 single containers, have landed in Bangladesh’s Chittagong Port, but the contents are not known.

The Indian and international concern in the matter flows from the past, when in 2014, the authorities seized a shipload of containers carrying ISI-supplied weapons for terrorists working against Bangladesh and, of course, India. As if to pretend that normalcy was fast returning to bilateral relations and that they had established ‘cultural relations’, which were at the centre of political differences in the seventies, Pakistani singer Rahat Fateh Ali Khan gave a concert in Dhaka on December 21.

It was a follow-up on the first meeting between PM Sharif and Yunus, with indications of more of the kind to follow in the coming weeks and months. In the immediate future, it remains to be seen if Islamabad would be ready to host a Bangladeshi singer, who would invariably perform in Bengali language, unlike the visitor, who sang mostly in Urdu. The reasons are not far to seek. As a part of the cultural conflict leading up to the 1971 war, linguistic differences between East and West Pakistan, between Bengali and Urdu, dictated the course of politics on both sides.

Responsibility to Protect

From a contemporary ‘majoritarian’ Bangladesh perspective, ‘giving back’ to India is at the top of everyone’s mind. Targeting the nation’s minority communities, namely Hindus, Buddhists, and Christians, seems to be coming naturally to a majority of those that had participated in the anti-Hasina protests in that country.

It is obvious that no senior leader in the government or outside has condemned the attacks on the nation’s minorities since Hasina’s ouster. The fact that she re-amended the Constitution to restore the nation’s ‘secular’ character after predecessors had changed the parent statute to make it an ‘Islamic’ Bangladesh too would have been recalled in internal cabals, ad infinitum.

The attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh were problematic for India, and New Delhi did not flinch from expressing its disapproval in public. It’s like India protesting the attack on the citizens of East Pakistan in the early seventies and on the Tamil minorities in Sri Lanka a decade later. After all, Bangladesh, even under Hasina, too had kind of protested at the violence on Muslims in India.

According to media reports, outgoing US National Security Advisor (NSA) Jake Sullivan has talked to Yunus and ticked off the Bangladesh government to ensure the safety and security of the minorities in the country. It was indicative of the way geopolitics has played out in this region in the post-Cold War era.

In the Cold War era, it was a case of the US administration of President Richard Nixon threatening New Delhi with the Seventh Fleet when India was fighting a war to ensure the safety and security of Pakistan’s ‘linguistic minorities’ in the nation’s eastern wing. It was possibly the first instance of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P) doctrine, which the US took decades more to adopt.

Unsettling effect

The post-Hasina developments in Bangladesh and relating to the country have an unsettling effect not only in the country—at least until a democratically elected stable government is put in place. The Yunus dispensation continues to remain unclear about it. It’s possibly a calculated move to keep the nation on the boil.

But the problem does not end there. The anti-India, anti-minorities vitriol that has found venomous expression both on the streets and in government corridors can lead to more problems, not less. If the current rulers want it that way, want to keep the nation unstable for whatever reason, it is not clear if they are conscious about it and also have plans to keep it that way for a longer time than otherwise expected.

The current bonhomie with Pakistan, in the light of past experiences with Bangladesh’s Islamist parties and terror groups, can act in one of five different ways. One, as groups, if not as a nation, they can revive anti-India terror acts across the shared borders. Two, they can try and work for reuniting the two wings of Pakistan, which may sound preposterous just now, but remember that these groups have not forgiven their peers from the past for creating an independent Bangladesh in the first place.

There is a third possibility. The Islamist groups in Bangladesh want to turn the nation into another Afghanistan, pre-US exit. Or, fourth, turn it into another Afghanistan, but after the US troops had left and the ruling Taliban made it a theological nation all over again, with Islamic laws that curtail human freedoms, starting with women.

A fifth possibility is of Islamists in the government and outside facing tough resistance from inherently democratic groups and leaders, whom the former would not hesitate to brand as pro-Hasina, pro-India, or both. Barring the fifth one, or even including it, there is the unsaid anti-India stance that could pour over into the streets and/or across the border in the form of terror attacks, aided and abetted by the Pakistani ISI.

That is not all. India and China have now sought to ease tension along their borders after recent confabulations. Until these negotiations are fast-tracked and produce positive outcomes at every turn, there will always be the Indian street apprehension about Beijing playing out another Doklam, another Galwan. Given their ideological mooring and larger-than-life projections of being the only ‘nationalist force’ in the country, this could put pressure on the current dispensation in New Delhi.

Lurking from behind but far away is the possible fallout of the increasing civil war situation in Myanmar, with which, too, India shares a 1643-kilometre border across four northeastern states: Arunachal Pradesh (520 km), Nagaland (215 km), Manipur (398 km), and Mizoram (510 km). The internal situation within Myanmar being what it is, news reports have spoken about the Indian security forces alerting the government about possible fallouts, involving more weapons reaching the hands of what they dub as ‘terrorists’ in these parts. The internal situation, especially in states like Manipur, over the past year and more is not something great to write about, either.

Then, there are the Rohingya refugees camping in Bangladesh in their lakhs, joining the local Islamists and training their anger against India in the name of religion. In both cases, the security agencies have reportedly not ruled out the possibility of modern weapons in the hands of the Arakan Army rebels in Myanmar reaching these other groups in and along the Indian borders.

Where does it all lead to? Anti-India developments in Bangladesh have almost overnight converted the entire South Asian land borders from Afghanistan to Myanmar into something more unsettling than it was already. In the midst of it all, New Delhi will have to make a careful decision on the Yunus dispensation’s demand for Hasina’s extradition.

Already, the Dhaka government has referred to the existing bilateral extradition treaty and also claimed that it does not refer to any proven court case in one country for it to seek the extradition of individuals from the other nation. At this stage, India cannot be seen as letting down an ally from the past, that too a woman leader, whom her imposter replacements want eliminated along with memories of her family.

On the other hand, any denial of an extradition request relating to Hasina could raise questions about India’s sincerity while enforcing similar demands from such other nations with which it has signed extradition treaties or is otherwise bound by international law to hand over to prosecutors elsewhere. More importantly, New Delhi’s long-pending demand for the extradition of anti-India terrorists, personified by the name and face of Dawood Ibrahim, could fall flat.

It’s not an easy question for the Modi government to find an answer for. But it cannot skip the question, either, for long.

The writer is a Chennai-based Policy Analyst and Political Commentator. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

&w=1200&resize=1200,675&ssl=1)

Post Comment